| Feature Stories: |

| January 11: The January issue of American Cinematographer Magazine contains a very interesting, detailed article about Quills, including a few new photos from the set. The article and pics are posted on a separate page - Go Here! Excerpt: |

|

"We wanted to give the impression that the walls were alive and dripping with madness," says [Production Designer Martin] Childs with a delighted laugh. "What was fantastically helpful to me - though probably not to anybody who had to schedule the film - was that Kaufman wanted to shoot the film in [continuity]. So we were adding green and decay as the story happened, a luxury we're normally never allowed. We were, for the first time in my experience, able to make a set live." |

| December 22: My pal Sylvia, who has the great site Dougray Scott in Focus, scanned this article for us from Film Review magazine's special issue - 'The Essential 2001 Preview': |

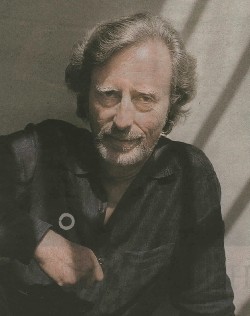

| Philip, it's been a long time since your last directorial effort. What was it about this material that you felt it was the right time to get back behind the camera? |

| Kaufman: It was just one of those fortuitous things. One day after seven years of searching for projects to do and having everything that I wanted to do come to naught and get caught in - for want of a better word - "development hell" over and over again, one day I heard this loud plopping sound outside my door. I opened the door, looked around, and there was this package in a brown paper wrapper with the cackling voice of the Marquis struggling to get out. (Grins) I read it and I just right away loved the writing, loved the story - I was chilled by it, was amused by it, and sat there rather stunned for about an hour thinking how would I make this…could I make this? |

| Given the state of American politics right now, is it the right time for a movie like this? |

| Kaufman: It's kind of amazing, isn't it, suddenly, that all sorts of issues that we discuss in this movie have come to the forefront. I mean, certainly the deep element of hypocrisy that is at the root of this piece - the Marquis' gleeful attacks on hypocrisy - seems to have deep relevance. When I read it, it was during the time of the Clinton-Ken Starr dance that they were doing at the time which was certainly brought to full culmination by the publication of that great book called The Starr Report, which brought all of those issues right into everybody's households including households with children in them. |

| Do you think that you responded to the material in part because of your experience with Henry and June, that having been the first NC-17 film that was supposed to be about art and ended up being attacked as if it was pornography? |

| Kaufman: I just respond to all kinds of things if they're good. I mean, people talk about Henry and June, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and Quills as meaning obviously I must be interested in… (Laughs) Look, I'm interested. I'm interested in sex, but no more so than any of you! Why don't we have more films that are adult, sexual-oriented, or about sex in America? |

| I just think Americans, given the chance to see these movies properly promoted and exploited - given a little bit of a build-up - maybe if one of these films appears every once in a while, they can just be knocked-off, so to speak. Like with Henry and June: the film was doing great business, and then suddenly in Boston and Texas they wouldn't allow it in theaters anymore! Blockbuster Video - even though they have sections for those off-color movies - still will not stock Henry and June, which is about writers and about serious, adult subjects. |

| Doug, why wasn't any of the Marquis' actual writing included in the script? |

| Wright: The reason that we didn't literally quote Sade is because most of the English translations are by a man named Austrin Wainhouse and we didn't have the rights to those translations. I also wanted to write stories that would further my narrative. But I have to say that the stories the Marquis tells in the tale: communion wafers are used in foreplay; rather insidious men dig up dead bodies in order to gratify themselves; and a wicked surgeon carves new orifices in a prostitute in order to reach his own level of sexual ecstasy. |

| So I think that the clips you hear in the film are emphatically true to his fiction. In fact, he was writing this epic novel, 120 Days of Sodom, and each day was supposed to be a new sexual atrocity acted out in this secluded chateau. And even with his prodigious imagination, he ran out of steam on about Day 89. So the last 30 days of that novel are fragments of stories he might have written had he the energy to finish it, and I took my tales from them and said, "You didn't finish them - I will!" So I hope that they reflect the full insidiousness, toxicity, and the very, very black wit of his work. |

| Philip, did you have to fight with the studio to get this made the way you wanted it to be? I'm sure you didn't want to go through anything like Henry and June again. |

| Kaufman: The script was sent to me by Fox Searchlight, so by the time I got into it there was a studio that wanted to do this, which in my experience was extraordinary. With Henry and June my wife and I took a year out of everything, just to sit and spend a year writing that and then trying to sell; fortunately, we were able to make that movie. But in this case, the gods shone upon us and sent us the Marquis de Sade! (Laughs) |

| Doug, how literally are we supposed to take the film's view of the Marquis de Sade? Is he symbolic of something or are we supposed to take this as the authorial opinion of him? |

| Wright: Well, I think that the Marquis de Sade is a very potent Rorschach and has been for a lot of writers. I think to suggest that our movie is the definitive portrait of Sade would be preposterous, because he's lost to us. In the last ten years alone there have been five new biographies that have debated his personality. |

| So I think I've done what other writers have done in the past, like Peter Weiss in Marat/Sade or Yukio Mishima in Madame de Sade. I've plucked the mythological Sade from history and plunked him down I hope in a parable about our time and the nature of violent art in an unstable culture. I've taken those aspects of Sade that most intrigued, titillated and appalled me - I've incorporated them into a character that I call Sade and placed him in our story. I think the writer or critic or academic to beware is the one who claims to have discovered the definitive Sade, because he's gone. I think that this is very much the Sade of Quills. |

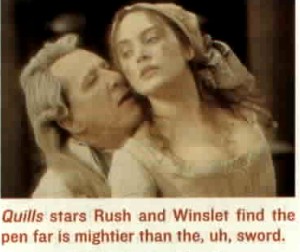

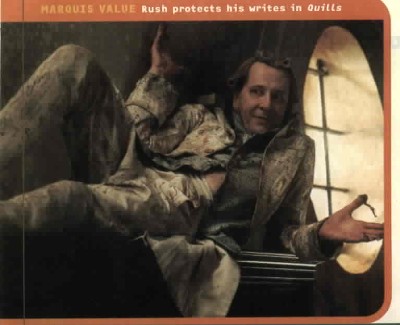

| Philip, what was it about Geoffrey Rush that drew you to have him play Sade? This is one of those roles that every actor must want to play. |

| Kaufman: The minute I read the script I also thought, I'm going to get great actors. And it did draw them - all as a labor of love. You think, who are the greatest actors of a certain age in the world? You start off with seven or eight people, then you think, who can do this language? And certain ones start dropping off. And then when I met Geoffrey by chance he was shooting a film here - he was in town and I said I'd like to meet him, because I think not only is he a great actor but every time I see him I don't recognize him. You know, one movie to the next, he's always - in other words, we have this, as Doug's describing, this mysterious Marquis, and the chance to have an actor who isn't readily identifiable in the starring role was great. Geoffrey had read the Marquis in college, he's lived this full life, he studied in France, he really didn't start acting in movies until he was in his early 40's, and he's very funny, he's physical, and the surprise I believe is that he's sexy. |

| Scenes like Geoffrey's full-frontal nudity - was that difficult? |

| Kaufman: Geoffrey is an actor absolute. He felt it was necessary to do it. When it came time to take off his clothes, as Jacqueline West the costume designer said, "Geoffrey, here's your final costume." And I would point out that in that moment, when he takes his clothes off and his wig, that's when the film becomes truly contemporary. That is a man of today and the only other man in the room is the Abbe, who's dressed in this Commes de Garcon abbey's outfit. You know, it could be of today - there's some churches in North Beach in San Francisco and I see guys walking around in very similar kinds of things. |

| So when the two of them are together in that room, I feel it becomes a very kind of contemporary kind of film. But I would point out that Geoffrey not only was comfortable with his nudity, but…half of the crew were woman - the assistant directors, there was a woman doing the boom - and everybody who had to be in the room, everybody was totally natural. It was shot in England and I don't' know if that would happen in other countries, but they all to a person loved the material, the subject matter, what it was saying, and Geoffrey was just sort of walking around. |

| There was no pressure on you to trim as it were the full-frontal nudity? One of the things about American films is that there's this great hypocrisy that you can have full-frontal female nudity but not the other way around. |

| Kaufman: No, we had no problems at all. To my mind, that shot just felt it - hopefully the ratings board felt that too - had a kind of a beauty and illustrated the loneliness. That shot in a way penetrates the man who was impenetrable and you feel that he's stripped of all things. I don't know. I heard the ratings board loved his penis, so… (Laughs) |

| Wright: I do think actually American movies are obsessed with sex, but as long as its infantilized, as long as it's Jason Biggs and an apple pie, or Cameron Diaz's hair. But I think what's exhilarating about Phil's work is that he's not afraid to present adults in erotic encounters, which seems absolutely unheard of in American movies. So I think that the teen market is saturated with what you would call sex films - much more overt sex films than ours, which is about the Marquis de Sade! |

| Could you talk about the relationship between the Marquis and the Abbe? |

| Wright: I think that the story between Geoffrey and Joaquin in the movie could be termed a kind of love story, and I think it takes that journey, and it never becomes physical but I think you get a sense of this bizarre and unsettling mutual attraction between the two of them and I think it reaches its crescendo in the scene where Sade is stripped of his clothing. I do hope that we get a sense of [the Marquis'] omnivorous omnisexuality, which I think was very much a part of his nature. Also, when the Abbe is leaving his room with the quills and he implores, "Well, bugger me then!" I hope that gives a sense that he was rapacious sexually and any number of characters in the film might fall prey to that. |

| The other thing that was very interesting was the amount of irony in Michael Caine's character, the fact that Sade talked rhetorically about Sadism but it seemed like everyone else practiced it. |

| Kaufman: Michael Caine - Reyer-Collard - is the Sadean hero. I mean, the Marquis says, "Ah, he's a man after my own heart!" It's almost as if he's the Frankenstein monster risen out of the Marquis' own literature come to drive him to his death. So we're now going back to an earlier question - it's not a biopic of the Marquis. Although Reyer-Collard was a real character - there's a street named after him in Paris - and Madeleine was a real character, the Abbe - although he was a four-foot hunchback - was a real guy too. |

| Then there's the question of art provoking violence. In the end, you can clearly argue that Sade's work provoked a great deal of tragedy and violence, but what point did you want the movie to make about that? |

| Kaufman: We wanted to give both arguments on either side of the censorship debate a full airing in the movie, the notion that violence in art can create violence in the culture and also the notion that art should always be unfettered and be allowed to reflect any aspect of the human experience. I think what we're trying to point to is an even larger truth that partisan argument doesn't allow, and that's that one of the great ironies in the history of art is that the oppressor is always the most reliable muse. |

|

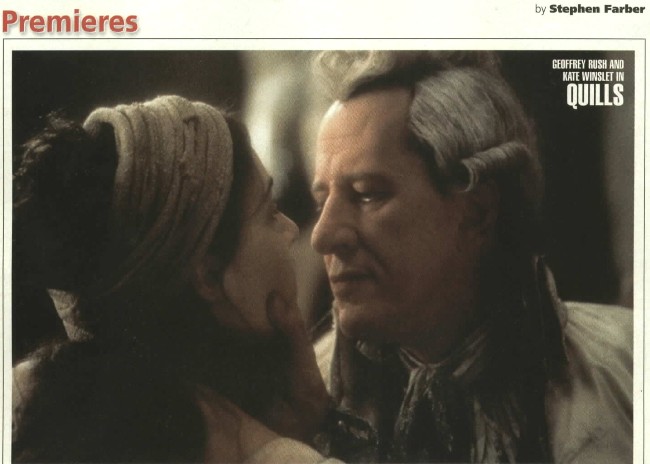

The timing couldn't have been better. It was almost as if the Hollywood-bashers in Washington had timed their salvo to tie in with Fox Searchlight's campaign for its fall release "Quills." The Federal Trade Commission issued its scathing report on Hollywood's sneaky practice of marketing films with extreme content to children on Sept. 11. And just a few days later director Philip Kaufman flew down to Los Angeles, from his home base in the legendary bohemian enclave of North Beach in San Francisco, to discuss his latest film, "Quills," an ink-black gothic farce about the extremes of free expression under siege. The film's irrepressible and monstrously entertaining centerpiece (portrayed with free-swinging relish by "Shine" Oscar-winner Geoffrey Rush) is none other than the Marquis de Sade, the 18th century pornographer and revolutionary misanthrope whose novels (including "Justine" and "120 Days of Sodom") have linked his name for all time with some of the rougher forms of off-center sexuality. |